https://chrisdaly1.substack.com/p/d-day-hemingway-and-gellhorn-at-war

Both writers, at war with each other, covered the invasion.

Jun 06, 2025

By Christopher B. Daly

[The following is an excerpt from a book in progress, titled The Democratic Art: The role of journalism in the rise of American Culture.]

HEM VS. GELL.

As writers, Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn both agreed, deep down, that writing fiction was a higher calling than reporting the news. Nevertheless, they both worked both sides of the street – journalism and fiction — for pretty much the duration of their careers.

In this excerpt, I want to zero in on a crucial period in the careers of these two writers. The time is D-Day – or June 6, 1944 – and the ensuing Allied invasion of the beaches of Normandy. At the time, they were married – to each other. Martha Gellhorn, then 35, was the third wife (of four) to Ernest Hemingway, then 44.

During their years together, from the first meeting in late 1936 until their divorce in late 1945, the two writers were not only lovers (sort of). But they were also literary rivals (for sure!).

They usually avoided competing head-to-head, but there was one occasion when they both covered essentially the same story at essentially the same time – that was the fateful invasion of Normandy in June 1944. We might ask: Who wrote it better?

A close reading of the journalism they produced around D-Day rewards readers with insight into both writers’ strengths, their weaknesses, and their styles. In the research for my book, I was struck by how different their approaches were and by how superior the work turned in by Gellhorn was.

THE STORY

In the fateful spring of 1944, Gellhorn was covering the Allied campaign to liberate Italy.

Hemingway was mostly avoiding covering the war – apparently content with already having made a name for himself as a figure associated with war. He had been wounded as an ambulance driver in WWI, he had covered the war in Spain for U.S. newspapers, and he had written two important (and best-selling) novels about war.

He stayed home in Havana – drinking to the point where he often started with a Scotch around 10 a.m. and ended the night by sleeping in his clothes, on the floor.

As for Gellhorn, as soon as the U.S. military relented in 1943 and began allowing women to report from the war zones controlled by the Allies, Gellhorn flew to London. She quickly got accredited as a war correspondent thanks to Collier’s magazine, where she had been writing for years. She headed to Italy – the fifth war she covered, after Spain, the Sudetenland, Finland, and China.

That was impressive, but her absence did not sit well with the Great Writer she had left behind in Havana. Finally, in exasperation, Hem sent a cable to Marty in 1943 with a blunt question:

“ARE YOU A WAR CORRESPONDENT, OR WIFE IN MY BED?”

Her answer: she would keep covering the war, filing dispatches to Collier’s from Europe and Asia. Gellhorn observed later that “My crime, really, was to have been at war when he had not.”

Still, she wanted to find some role for Hemingway in covering the great conflict. She even suggested that he might pitch a series to Collier’s, the popular national weekly magazine that employed her. If it worked, she knew full well that her famous husband would outrank her among the magazine’s correspondents; she also knew that each magazine got only one slot to cover the front lines, so it might cost her.

There are differing versions of exactly what happened next. One view is that Gellhorn offered Hemingway the chance to take her place as Collier’s front-line war reporter. The other version is that he went around her back to editors at Collier’s and talked them into letting him big-foot her off the momentous story.

In any case. From her letters it appears that Gellhorn regretted the switch, and she certainly came to resent Hemingway for it.

To set the scene . . . both came home to Cuba for a bit before deciding to head to England for the big Allied invasion.

Women were then banned from most flights across the Atlantic. So, while Hemingway flew to England, Gellhorn was relegated to going by ship. As it turned out, she was the only woman and the only civilian on a Norwegian freighter full of explosives crossing the North Atlantic. Thus, her ship was a prime target for Nazi submarines prowling the ocean.

Hemingway arrived in London well ahead of Gellhorn, and he was soon up to his old tricks. Hemingway was introduced to Mary Welsh, an attractive younger American journalist (who also happened to be somewhat married). They were soon carousing around London, as Hemingway enjoyed getting to know Mary, who clearly adored him.

(As Mary wrote: “I wanted him to be the Master, to be stronger and cleverer than I; to remember constantly how big he was and how small I was.”)

On May 25, 1944, while Gellhorn was still crossing the Atlantic, Hemingway attended a very boozy party in London hosted by the photographer Robert Capa. Hemingway got a ride home, but the driver crashed the car into a water tower, and Hemingway was thrown against the windshield, resulting in another of his many traumatic brain injuries. Among his hospital visitors was Mary Welsh of TIME magazine, who brought daffodils.

When Gellhorn arrived in London, she quickly sized up the situation and decided she had really had it with Hemingway – with all of his drinking, his lying, his cheating, and his bullying. She would have demanded a divorce right then, but she felt bad for the 57 stitches so recently etched into Hemingway’s head, and so she waited.

All that spring, the Allies were planning their big push from England into France. All of London, indeed all of England, was abuzz about the impending invasion, the largest amphibious assault in world history. Everyone knew it was imminent, but no one knew exactly when or where. The details were top secret.

Throughout May and early June, soldiers, officers, journalists, and others all knew that something epic was coming, but much still depended on the tides and the weather. In the final days, journalists were quietly tapped by military handlers and vanished, one by one, into the staging areas.

HIS STORY

The Allied public relations staff assigned Hemingway to cross the Channel on a big Navy ship. According to the plan, when they neared the coast of Normandy, Hemingway would be lowered into a landing craft skippered by Lieutenant Robert Anderson.

In the story that he wrote for Collier’s, Hemingway behaves (and writes) as if he outranks Anderson – offering to steer the ship and, if needed, command the whole invasion. As usual, Hemingway makes himself the main protagonist of his story, if not the hero. In his version, they end up mostly bobbing around in their landing craft, searching for the intended landing spot.

The landing craft, also known as Higgins boats, were 36 feet long, with sides made of plywood, equipped with an engine in the rear and a bow that could drop open to form a ramp. The boats could be driven into shallow water or right onto a beach.

The U.S. Navy purchased thousands of them to storm beaches from Normandy to Iwo Jima. Each boat could carry about three dozen soldiers. With the bow lowered, the men could charge down the ramp and into action. Those little boats tended to bounce around badly in choppy seas or high surf, and the wooden sides could not stop enemy fire. As a result, the ship’s bottom would often be shin-deep with a mix of seawater, blood, and vomit.

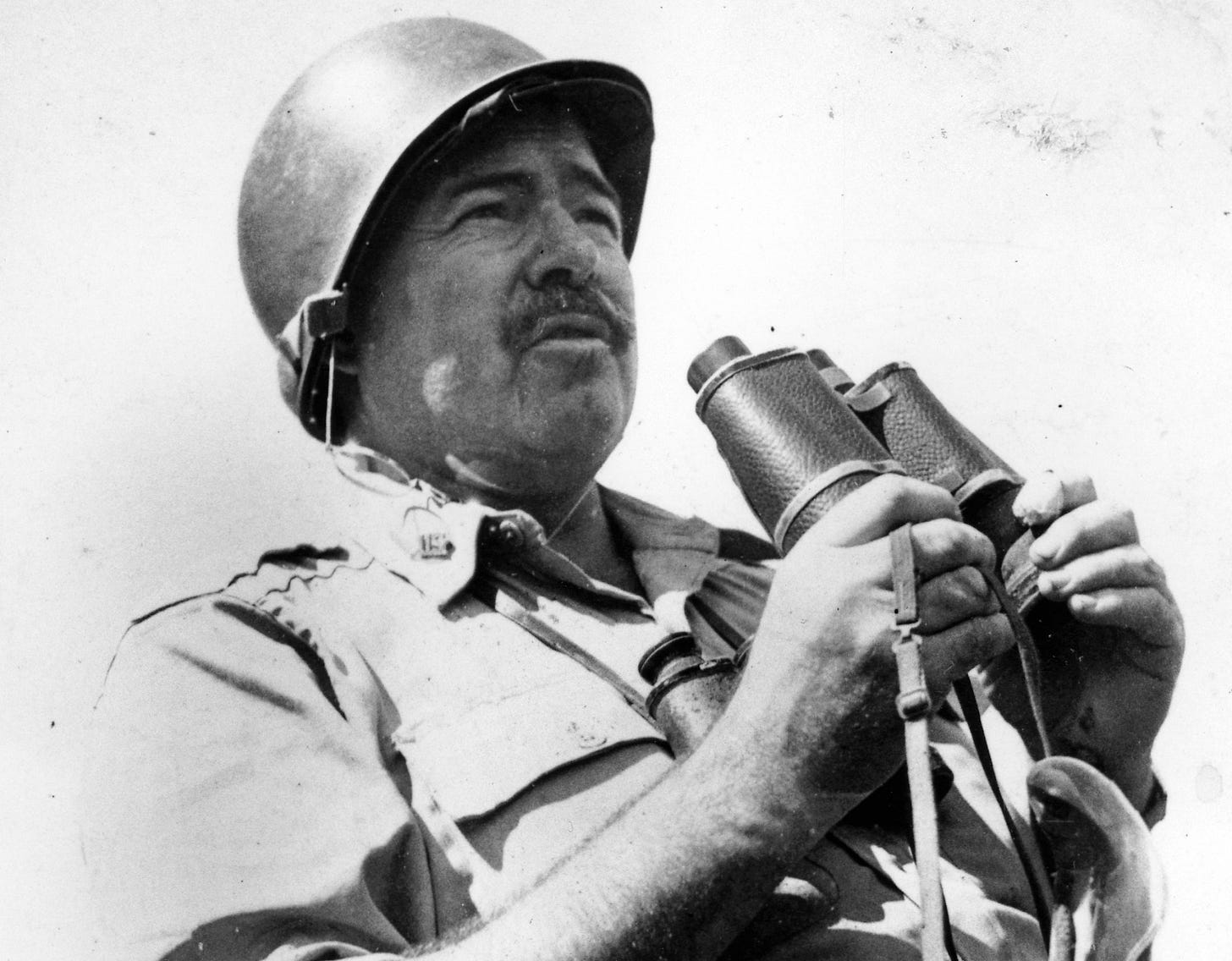

In Hemingway’s account, we see him using his own Zeiss binoculars, standing next to the skipper and conferring with him like a military peer. He quotes himself offering advice to Lt. Anderson, pointing out landmarks on the French coast, and trying to guide the boat to a section of Omaha Beach code-named Fox Green.

Thousands and thousands of words later, the landing craft gets near the beach and disgorges its platoon of fighting men.

Hemingway topped off his story with a deeply misleading final section. In it, he notes that the Germans kept firing their antitank guns and mortars from the cliffs above the beach. But the Americans kept coming.

In his final graf, Hemingway wrote: “It had been a frontal assault in broad daylight, against a mined beach defended by all the obstacles military ingenuity could devise. But every boat . . . had landed her troops and cargo. No boat was lost through bad seamanship. All that were lost were lost by enemy action. And we had taken the beach.” [emphasis added]

Now, that last line is really rich. When Hemingway wrote that “we” had taken the beach, he could not have meant that he was among the successful invaders, because he knew damn well that he had never left the boat — nor, much less, gone ashore.

To be fair, though, it was a common practice among U.S. journalists during World War II to say that “we” were doing this or that. So close was the identification of the press corps with the military corps, and so unified was the commitment to victory, that the usage became standard and drew almost no notice by 1944.

But Hemingway’s last statement – “We had taken the beach” – managed to be both true and misleading. It’s true that American troops had taken the beach, but by using the pronoun “we,” Hem was implying that he was among the “we” who had taken the beach. In all honesty, of course, it was they who took the beach.

In fact, Hem did not step foot on an invasion beach that day or any other. He made it back to London the same day and spent the night under clean sheets at the Dorchester Hotel in Mayfair.

Hemingway did not get to France until weeks later, safe and dry. Then, thanks to a U.S. general, the famous writer was provided with a captured German motorcycle that had a sidecar, plus a Mercedes convertible with his own driver.

HER STORY

As for Gellhorn, she was furious at Hemingway. As any journalist knows, the decent thing for him to have done would have been to find another magazine to write about D-Day for (Esquire, perhaps) and to have left Gellhorn in place as the top correspondent at Collier’s.

But no. He had to take her slot, then stash her at sea for three weeks while he partied in London and started romancing a new woman.

Gellhorn was also angry about the last-minute restrictions imposed by the Allied public relations command. They decreed that no women would be allowed to report on the first day of the invasion.

Instead, all the women reporters were shepherded into a giant press briefing center in London, along with any male reporters who were left behind. There, they were all locked in, and all fed the same official information about the invasion from Public Relations Officers.

As soon as the doors opened, Gellhorn began making her own way to the big story. Dressed in a standard-issue green correspondent’s uniform, she hitched a ride to one of the embarkation ports in southern England. There, she wrote a story on June 6 about the first batches of German POWs to reach England. But she was just getting started.

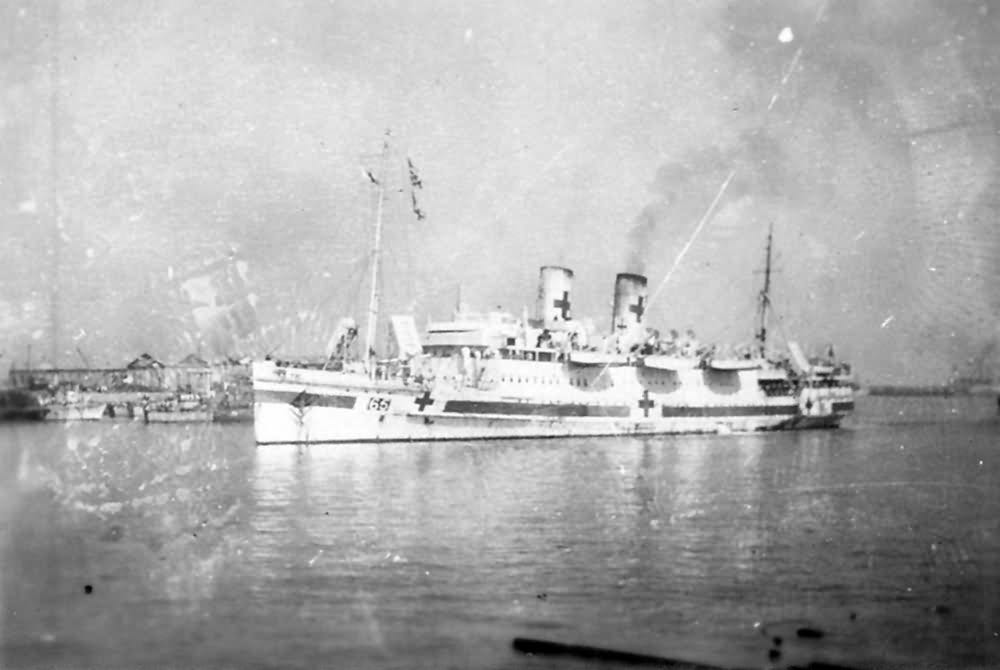

The next day, she found a hospital ship getting ready to cross the Channel to the invasion beaches. She talked her way on board, then locked herself in an empty bathroom and hid there until the ship was under way—so she could not be put ashore.

Painted white, the ship was under the command of the English merchant marine, not the U.S. Navy. As a result, Gellhorn was allowed to move about freely, to observe the action, and to interview nurses, doctors, patients, and prisoners.

The result was a magnificent piece of reporting.

In her story, Gellhorn began by noting that the white medical ship stood out in the armada of grey military ships “like a sitting pigeon” and that “there was not so much as a pistol on board in the way of armament.” Carefully, the medical ship picked a way through lanes in the sea that had been cleared of German mines.

“Then we saw the coast of France and suddenly we were in the midst of the armada of the invasion.” She noted the stunning number of ships as well as the planes and barrage balloons overhead (“looking like comic toy elephants”). Gellhorn also noted the constant booming of naval weapons all around.

Then, the first of the wounded began to arrive. Small ships called “water ambulances” were beginning to scour the surf and the beaches, looking for wounded combatants to bring them to the large floating hospital. There, a wooden box, “looking like a lidless coffin,” was lowered over the side, to bring the wounded aboard the hospital ship.

As it turned out, the first soldier was German. No matter. The medical team went right to work. Gellhorn went on to describe horrible injuries suffered by U.S. soldiers – gaping untreated wounds, shattered bones, missing body parts.

Around sunset, she went ashore herself at “Easy Red” beach with a medical team and set to work as a stretcher-bearer. She was now the only woman among the invading force of hundreds of thousands of men.

Staying in the narrow, marked lanes that had been cleared of mines, Gellhorn pitched in and helped move bodies in the dark to designated pickup spots.

All the while, German sniper fire and the occasional anti-aircraft battery kept up the roar of war. “Everyone agreed that the beach was a stinker and it would be a great pleasure to get the hell out of here sometime.”

Eventually, she decided to leave. She boarded a landing craft, at the edge of the beach. It was loaded with the wounded and was heading back out to the hospital ship, anchored in deeper water.

Gellhorn looked back toward the beach, where bonfires were roaring. “The beach, in this light, looked empty of human life, cluttered with dark square shapes of tanks and trucks and jeeps and ammunition boxes and all the motley equipment of war. It looked like a vast uncanny black-and-red flaring salvage dump, whereas once upon a time people actually went swimming here for pleasure.”

Gellhorn had gone ashore, under fire, and served as an eye-witness to history from one of the invasion beaches – all things that her famous, macho husband had not done.

Gellhorn had beaten Hemingway to France.

A CODA

Six months later, they were divorced. . . .

[THE BACKSTORY: For some years now, I have been working on a book that I am calling The Democratic Art. In it, I look at the careers of many of the top figures in American literature and the visual arts and draw attention to their apprenticeships in journalism.]

Discussion about this post

CommentsRestacks

TopLatestDiscussions

FOR SALAMANDERS, THE ‘BIG NIGHT’ IS EVERYTHING

WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM HUMANS, SLIMY AMPHIBIANS MEET AND MATE, THEN SEPARATE

Apr 22•

Sketching for newspapers shaped his fine art

Feb 24•

Langston Hughes and the train ride that changed his life.

Apr 27

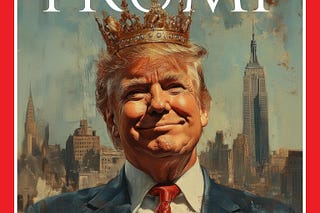

Walt Whitman warned us about “King Donald”

And the poet lamented the dying of our democracy in 1855

Feb 23•

On this Patriot’s Day, some thoughts on another red-haired dictator

Apr 19•

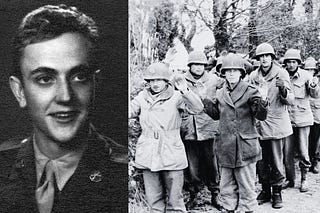

How a young Kurt Vonnegut got into one of the worst horrors of WWII

May 5

KURT VONNEGUT, YOUNG JOURNALIST

Apr 3•

© 2025 Chris Daly

Privacy ∙ Terms ∙ Collection notice

Substack is the home for great culture